Simona Andrioletti

Defence14 October 2021 ︎︎︎ 30 January 2022

di Jessica Bianchera

“Si possono fare molti usi delle innumerevoli opportunità che la vita moderna fornisce per guardare – a distanza, attraverso il mezzo fotografico – il dolore degli altri. Le fotografie di un’atrocità possono suscitare reazioni opposte. Appelli per la pace. Proclami di vendetta. O semplicemente la vaga consapevolezza, continuamente alimentata da informazioni fotografiche, che accadono cose terribili”. (Susan Sontag, Davanti al dolore degli altri, Milano: nottetempo, 2003, p.23)

“In fact, there are many uses of the innumerable opportunities a modern life supplies for regarding – at a distance, through the medium of photography – other people’s pain. Photographs of an atrocity may give rise to opposing responses. A call for peace. A cry for revenge. Or simply the bemused awareness, continually restocked by photographic information, that terrible things happen.” (Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others)

Sfogliando i quotidiani, guardando i telegiornali, camminando per strada o navigando nel web, le “opportunità”, come dice Susan Sontag, di trovarci “davanti al dolore degli altri” sono moltissime: distruzioni, bombardamenti, violenze su uomini e donne, guerre, pandemie, disastri ambientali, aggressioni, invasioni, episodi di violenza esplicita o subdolamente mascherata. Nelle società contemporanee, in cui i mezzi di informazione hanno un ruolo centrale, il dolore degli altri è “uno spettacolo” all'ordine del giorno.

Quale effetto produce su di noi il dolore degli altri? Si tratta effettivamente di qualcosa estraneo dai noi, che non ci riguarda? Che ruolo riveste l’immagine nel documentare e comunicare la pervasività degli innumerevoli episodi di violenza pubblica, privata, singolare, collettiva, sistemica? Riusciamo a entrare in diretta empatia con il dolore degli altri o ne siamo ormai profondamente assuefatti? Nel suo libro la Sontag si interroga sul modo in cui le immagini influenzano la nostra percezione di quanto accade, formano le opinioni comuni, inducono a contrastare i conflitti bellici o a sostenerli.

Dalla guerra civile spagnola a Dachau a Auschwitz, dalla Cambogia alla Bosnia al Rwanda all'11 settembre: Sontag si sofferma sulle immagini che hanno assunto valore emblematico e mostra come hanno condizionato le nostre idee, le nostre credenze, le nostre passioni, la nostra percezione della società civile e del ruolo che svolgiamo in essa.

Con lei e dopo di lei molti si sono interrogati e si interrogano sulla relazione tra violenza, immagine e informazione, spostando sempre più il baricentro dell’attenzione dai fatti alla loro elaborazione estetizzante o narrativa, alla strumentalizzazione dell’immagine che diventa mezzo per la costruzione di precise narrazioni. Esiste un’intera tradizione della cosiddetta “estetica della violenza” che interessa la storia, la politica, la cultura di massa, il cinema, l’arte, dai sistemi di propaganda ai reportage giornalistici alla fiction, con ampi margini di sovrapposizione tra questi, complicando sostanzialmente la nostra capacità di distinguere la realtà dalla finzione, di reagire emotivamente e di agire fattivamente se messi in relazione con episodi e situazione di violenza.

C’è chi assiste a episodi di violenza con il cellulare in mano, per immortalare la scena; c’è chi semplicemente non è più in grado di riconoscerla; c’è chi reagisce con lo stesso mezzo e uguale misura alimentando il concatenarsi e il diffondersi di dinamiche di sopraffazione; c’è chi non conosce alternative alla violenza perché ci vive e ci è cresciuto ed è l’unico linguaggio che gli è stato da sempre proposto per relazionarsi al mondo.

Quale effetto produce su di noi il dolore degli altri? Si tratta effettivamente di qualcosa estraneo dai noi, che non ci riguarda? Che ruolo riveste l’immagine nel documentare e comunicare la pervasività degli innumerevoli episodi di violenza pubblica, privata, singolare, collettiva, sistemica? Riusciamo a entrare in diretta empatia con il dolore degli altri o ne siamo ormai profondamente assuefatti? Nel suo libro la Sontag si interroga sul modo in cui le immagini influenzano la nostra percezione di quanto accade, formano le opinioni comuni, inducono a contrastare i conflitti bellici o a sostenerli.

Dalla guerra civile spagnola a Dachau a Auschwitz, dalla Cambogia alla Bosnia al Rwanda all'11 settembre: Sontag si sofferma sulle immagini che hanno assunto valore emblematico e mostra come hanno condizionato le nostre idee, le nostre credenze, le nostre passioni, la nostra percezione della società civile e del ruolo che svolgiamo in essa.

Con lei e dopo di lei molti si sono interrogati e si interrogano sulla relazione tra violenza, immagine e informazione, spostando sempre più il baricentro dell’attenzione dai fatti alla loro elaborazione estetizzante o narrativa, alla strumentalizzazione dell’immagine che diventa mezzo per la costruzione di precise narrazioni. Esiste un’intera tradizione della cosiddetta “estetica della violenza” che interessa la storia, la politica, la cultura di massa, il cinema, l’arte, dai sistemi di propaganda ai reportage giornalistici alla fiction, con ampi margini di sovrapposizione tra questi, complicando sostanzialmente la nostra capacità di distinguere la realtà dalla finzione, di reagire emotivamente e di agire fattivamente se messi in relazione con episodi e situazione di violenza.

C’è chi assiste a episodi di violenza con il cellulare in mano, per immortalare la scena; c’è chi semplicemente non è più in grado di riconoscerla; c’è chi reagisce con lo stesso mezzo e uguale misura alimentando il concatenarsi e il diffondersi di dinamiche di sopraffazione; c’è chi non conosce alternative alla violenza perché ci vive e ci è cresciuto ed è l’unico linguaggio che gli è stato da sempre proposto per relazionarsi al mondo.

Leafing through the newspapers, watching the news, walking down the street or surfing the web, the “opportunities”, as Susan Sontag says, to find ourselves in the face of “other people’s pain” are numerous: destruction, bombing, violence against men and women, wars, pandemics, environmental disasters, assaults, invasions, episodes of explicit or subtly disguised violence. In contemporary societies, in which the media have a central role, the pain of others is “a show” on the agenda.

What effect does this pain have on us? Is it actually something foreign to us, does it not concern us? What role does the image play in documenting and communicating the pervasiveness of the countless episodes of public, private, singular, collective, systemic violence? Are we able to enter into direct empathy with other people’s pain or are we now deeply accustomed to it? In her book, Sontag questions the way in which images affect our perception of what is happening, form common opinions, lead us to deplore war conflicts or to commend them.

From the Spanish Civil War to Dachau and Auschwitz, from Cambodia to Bosnia, to Rwanda, to 11 September: Sontag focuses on images that have assumed an emblematic value and shows how they influenced our ideas, our beliefs, our passions, our perception of civil society and the role we play in it. With her and after her, many have questioned and interrogated themselves about the relationship between violence, image, and information, by increasingly shifting the focus from the facts to their aesthetic or narrative processing, to the exploitation of the image that becomes a means for construction of precise narratives.

There is an entire tradition of the so-called “aesthetics of violence” that affects history, politics, mass culture, cinema, art, from propaganda systems to journalistic reports to fiction, which often overlap and as a consequence substantially complicate our ability to distinguish reality from fiction, to react emotionally and to act effectively when we face episodes and situations of violence.

There are those who witness episodes of violence with smartphones in their hand, to immortalize the scene; there are those who simply are no longer able to recognize it; there are those who react with the same means and measure and stoke the concatenation and spread of dynamics of oppression; there are those who do not know alternatives to violence because they have lived and grown up in such contexts and then violence is the only language that has always been proposed to them to relate to the world.

What effect does this pain have on us? Is it actually something foreign to us, does it not concern us? What role does the image play in documenting and communicating the pervasiveness of the countless episodes of public, private, singular, collective, systemic violence? Are we able to enter into direct empathy with other people’s pain or are we now deeply accustomed to it? In her book, Sontag questions the way in which images affect our perception of what is happening, form common opinions, lead us to deplore war conflicts or to commend them.

From the Spanish Civil War to Dachau and Auschwitz, from Cambodia to Bosnia, to Rwanda, to 11 September: Sontag focuses on images that have assumed an emblematic value and shows how they influenced our ideas, our beliefs, our passions, our perception of civil society and the role we play in it. With her and after her, many have questioned and interrogated themselves about the relationship between violence, image, and information, by increasingly shifting the focus from the facts to their aesthetic or narrative processing, to the exploitation of the image that becomes a means for construction of precise narratives.

There is an entire tradition of the so-called “aesthetics of violence” that affects history, politics, mass culture, cinema, art, from propaganda systems to journalistic reports to fiction, which often overlap and as a consequence substantially complicate our ability to distinguish reality from fiction, to react emotionally and to act effectively when we face episodes and situations of violence.

There are those who witness episodes of violence with smartphones in their hand, to immortalize the scene; there are those who simply are no longer able to recognize it; there are those who react with the same means and measure and stoke the concatenation and spread of dynamics of oppression; there are those who do not know alternatives to violence because they have lived and grown up in such contexts and then violence is the only language that has always been proposed to them to relate to the world.

DEFENCE è uno stato di necessità, un invito a guardare davvero: viviamo in un mondo che ignoriamo più o meno consapevolmente al fine di preservare uno stato di quiete apparente mentre fuori infuria la tempesta. È questo lo strumento di miglior difesa che siamo in grado di mettere in campo? È la violenza intrinsecamente insita nella natura umana? Esiste una giustificazione alla violenza? Come ci si difende quando sembra che il mondo intero stia implodendo su se stesso? Quali saranno le conseguenze dei fatti che stiamo ignorando oggi? Simona Andrioletti non fa che porci domande, che collocarci davanti ai fatti, quegli stessi fatti che cerchiamo con impegno di ignorare per raccontarci una realtà non edulcorata in cui non esiste sostanziale differenza tra la potenza devastatrice di un’invasione di cavallette come quella avvenuta nel Corno d’Africa nel 2020, secoli di sopraffazione colonialista più o meno esplicita, depauperazione delle risorse da parte dei paesi cosiddetti “avanzati”, turismo voyeuristico per super ricchi in paesi in cui la popolazione muore di fame (Greetings from Kenya to Europe, 2020).

Così come altrettanto indifesa e fragile si presenta l’esistenza di un’intera generazione che ha ereditato dalle precedenti un mondo in piena crisi ecologica ed economica in cui non esistono certezze e in cui l’adolescenza è privata di quella spensieratezza che gli adulti sommariamente assegnano a questa fase della vita: giovani che crescono senza una guida e un punto di riferimento, vittime di violenza o cresciuti in contesti violenti, o più semplicemente pervasi da una sensazione inafferrabile di mancanza di senso, aggravata da due anni di isolamento e pandemia, senza altro rifugio che la dimensione virtuale e fittizia del web. Dai macroeventi al sottile incrinarsi delle emozioni, non c’è difesa e non c’è appello.

Così come altrettanto indifesa e fragile si presenta l’esistenza di un’intera generazione che ha ereditato dalle precedenti un mondo in piena crisi ecologica ed economica in cui non esistono certezze e in cui l’adolescenza è privata di quella spensieratezza che gli adulti sommariamente assegnano a questa fase della vita: giovani che crescono senza una guida e un punto di riferimento, vittime di violenza o cresciuti in contesti violenti, o più semplicemente pervasi da una sensazione inafferrabile di mancanza di senso, aggravata da due anni di isolamento e pandemia, senza altro rifugio che la dimensione virtuale e fittizia del web. Dai macroeventi al sottile incrinarsi delle emozioni, non c’è difesa e non c’è appello.

DEFENCE is a state of necessity, an invitation to really look: we live in a world that we more or less consciously ignore in order to preserve a state of apparent stillness while the storm rages outside. Is this the best defence tool we can use? Is violence inherently intrinsic in human nature? Is there a justification for violence? How do you defend yourself when it seems the whole world is imploding on itself? What will be the consequences of the facts we are ignoring today? Simona Andrioletti does nothing but ask us questions, place us in front of the facts, those same facts that we try hard to ignore, to tell us about an unsweetened reality in which there is no substantial difference between the devastating power of an invasion of locusts like the one that took place in Horn of Africa in 2020, centuries of more or less explicit colonialist oppression, depletion of resources by the so-called “advanced” countries, voyeuristic tourism for the super-rich people in countries where the population is dying of hunger (Greetings from Kenya to Europe).

Just as defenceless and fragile as the existence of an entire generation is, which has inherited from its predecessors a world in full ecological and economic crisis in which there are no certainties and in which adolescence is deprived of that light-heartedness that adults summarily assign to this stage of life: young people who grow up without a guide and a point of reference, victims of violence or raised in violent contexts, or more simply pervaded by an elusive feeling of lack of meaning, aggravated by two years of isolation and pandemic, without another refuge than the virtual and fictitious dimension of the web. From macro events to the subtle cracking of emotions, there is no defence and there is no appeal.

Just as defenceless and fragile as the existence of an entire generation is, which has inherited from its predecessors a world in full ecological and economic crisis in which there are no certainties and in which adolescence is deprived of that light-heartedness that adults summarily assign to this stage of life: young people who grow up without a guide and a point of reference, victims of violence or raised in violent contexts, or more simply pervaded by an elusive feeling of lack of meaning, aggravated by two years of isolation and pandemic, without another refuge than the virtual and fictitious dimension of the web. From macro events to the subtle cracking of emotions, there is no defence and there is no appeal.

Il nucleo tematico e concettuale del lavoro di Simona Andrioletti per DEFENCE si materializza nei 10 minuti e 42 secondi di Defence. What do you do with your anger?, un collage di found footage in cui assistiamo al susseguirsi di immagini che documentano situazioni di sopraffazione fisica, emotiva e ambientale. La violenza che infuria nella potenza devastatrice della natura e quella che si scatena immotivatamente e senza alcun senso sugli spalti di uno stadio gremito di gente; la lotta di due bambini nella piscina di casa a cui chi filma assiste impassibile e il senso di autodistruzione di un uomo che in pochi minuti trangugia intere bottiglie di vodka; la folla in delirio che perde il controllo durante un rave e una rissa tra due ragazzini che si massacrano di botte sotto lo sguardo divertito di chi con il cellulare registra la scena; l’esplosione di un ponte in un boato fragoroso e le parole amare di Umberto Galimberti: “Se guardo avanti, il futuro non è più una promessa ma è una minaccia e allora io vivo il presente in presa diretta 24 ore su 24 dando espressione a tutta la mia forza e a tutta la mia potenza, e mi anestetizzo dallo sguardo sul futuro per non andare in angoscia, per non assaporare quotidianamente la mia insignificanza sociale”.

The thematic and conceptual core of Simona Andrioletti’s work for DEFENCE materializes in the 10 minutes and 42 seconds of Defence. What do you do with your anger?, a collage of found footage in which we witness the succession of images that document situations of physical, emotional and environmental overwhelm. The violence that rages in the devastating power of nature and the one that unleashes without reason and without any sense on the bleachers of a stadium full of people; the struggle of two children in the swimming pool of the house to which the filmmaker watches impassively and the sense of self-destruction of a man who in a few minutes gulps down entire bottles of vodka; the delirious crowd that loses control during a rave and a fight between two kids who beat each other under the amused gaze of those who record the scene with their mobile phones; the explosion of a bridge in a thunderous roar and the bitter words of Umberto Galimberti: “If I look ahead, the future is no longer a promise but a threat and then I live the present live 24 hours a day, giving expression to all my strength and all my power, and I anesthetize myself from the gaze on the future in order not to go into anguish, not to savour my social insignificance every day.”

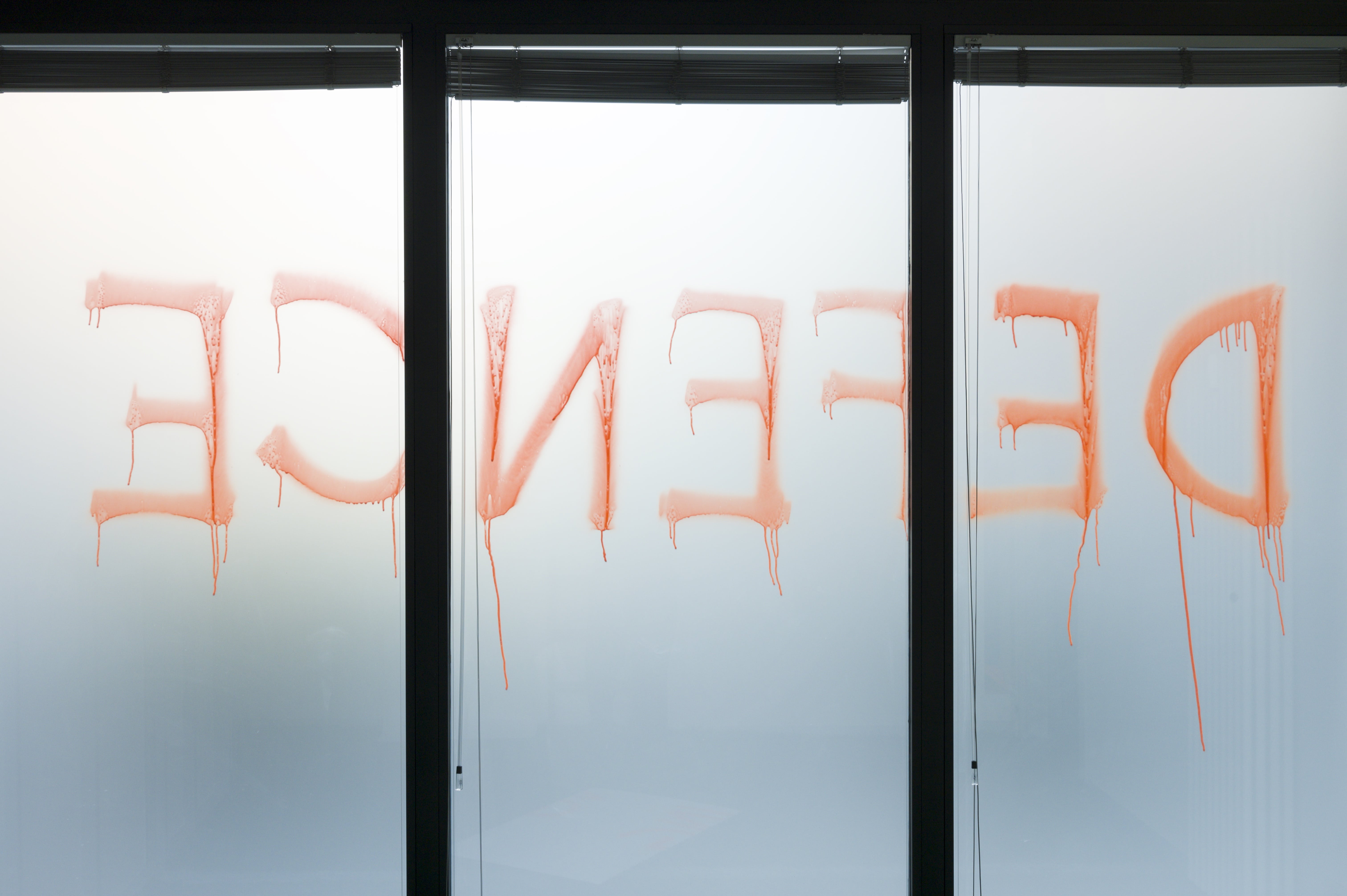

Questo immaginario complesso esplode e si moltiplica nello spazio della mostra attraverso immagini, simboli e feticci che non hanno nulla a che vedere con quell’ “estetica della violenza” di cui si accennava ma, anzi, si allontanano il più possibile dal perverso desiderio di provocare un piacere estetico che ossessivamente il pubblico chiede all’oggetto artistico. La mostra si costruisce piuttosto come un dispositivo carico di rimandi più o meno espliciti o sottesi che parte prima di tutto dal gesto dissacratorio sulla vetrina, vandalizzata con la scritta “DEFENCE” su tutta la sua estensione, e si sviluppa all’interno con una profonda trasformazione degli spazi. Il piano terra, rivestito con erba sintetica e disseminato di elementi che provengono dal mondo calcistico, rievoca la competitività dello sport che da contesto ludico e aggregativo si trasforma in occasione di scontro violento (Verona e la sua curva estremista dell’Hellas ne sanno qualcosa). Una valenza doppia per questa porzione di campo, che dalle devianze dei grandi stadi sposta l’attenzione sui campetti di quartiere, spesso unico luogo di aggregazione giovanile. L’indagine sulla condizione esistenziale dei ragazzi in età adolescenziale si configura come uno dei temi dominanti della mostra e della ricerca della Andrioletti, la quale ne osserva e ne studia le dinamiche di relazione anche attraverso laboratori, workshop e progetti condivisi che le permettono di entrare in dialogo diretto e non mediato con quelle generazioni e quei contesti sociali che più meriterebbero attenzione e che meno vengono spesso considerati. AVE MARIA (Thinking of Caravaggio) e STELLA MAGAZINE (realizzati rispettivamente con la collaborazione di Riccardo Rudi e Jonas Höschl - Felix Naumann secondo una prassi collaborativa di ibridazione delle pratiche e contaminazione di linguaggi che è tipica del lavoro dell’artista) nascono proprio da un contesto laboratoriale realizzato a Verona con i ragazzi di alcune comunità e centri di aggregazione per ragionare sulle pratiche artistiche partecipative, la gestione della rabbia, la cultura come strumento di riscatto sociale che ha portato a un reciproco scambio di valori e prospettive con particolare attenzione per le subculture del web, dei social, della musica e della cultura trap come strumenti di espressione di un disagio umano ed esistenziale che giace invisibile e inascoltato eppure reale e profondamente radicato. Un disagio che si estende al di fuori dal contesto di appartenenza e si realizza nella quotidianità quando si trasforma in depressione adolescenziale analizzata in DIPTYCH (Thoughts on time perception): gli effetti della pandemia da Covid-19 e dell’isolamento si palesano nella relazione tra due adolescenti, sottratti al normale sviluppo delle dinamiche di gruppo e dei rapporto interpersonale tra pari, in una fase della vita in cui la percezione di ogni evento e dello stesso trascorrere del tempo appare enormemente amplificato, dilatato, intensificato. Significativamente l’opera si svolge come un dittico, mutuando la struttura di un’icona sacra medievale, di quelle che si potevano facilmente chiudere e portare con sé in caso di assedio o di fuga improvvisa. All’iconografia classica di santi e martiri si sostituiscono le fotografie di due giovani durante un videochiamata lunga una giornata interna, come la precedente e la successiva: una relazione che si consuma nella sfera virtuale anche se a separarli sono solo pochi chilometri di distanza. Sulle pareti esterne dell’asettico dittico, appositamente realizzato con materiali freddi come l’acciaio e il plexiglass, sono incisi al laser due emoji (un cuore infuocato) e testi tratti dalle canzoni degli artisti americani Lil Peep e Juice Wrld, a costruire un nuovo codice di riferimenti iconografici e verbali per una nuova generazione che non si identifica più in simboli e valori appartenenti a un passato ormai anacronistico.

This complex imaginary explodes and multiplies in the space of the exhibition through images, symbols and fetishes that have nothing to do with that “aesthetic of violence” mentioned above but, on the contrary, move as far away as possible from the perverse desire to provoke an aesthetic pleasure that the audience obsessively requires of the artistic object. The exhibition is rather built as a device full of more or less explicit or unexpressed references that starts first of all from the desecrating gesture on the window, vandalized with the writing “DEFENCE” over its entire extension, and develops inside with a profound transformation of spaces. The ground floor, covered with synthetic grass and scattered with elements that come from the football world, recalls the competitiveness of sport that from a playful and aggregative context is transformed into an occasion of violent confrontation (Verona and its Hellas hooligans know something about it). There is a double value for this part of pitch, which shifts attention from the deviations of the large stadiums to the neighbourhood pitches, which are often the only gathering place for young people. The investigation into the existential condition of adolescents is configured as one of the dominant themes of exhibition and research of Andrioletti, who observes and studies their relationship dynamics also through workshops and shared projects that allow her to enter in direct and non-mediated dialogue with those generations and those social contexts that most deserve attention and that are often less considered. Ave Maria (Thinking of Caravaggio) and Stella Magazine (created respectively with the collaboration of Riccardo Rudi and Jonas Höschl – Felix Naumann, according to a collaborative procedure of hybridization of practices and contamination of languages that is typical of the artist’s work) stem from a workshop context activated in Verona with young people from some communities and aggregation centres to think about participatory artistic practices, anger management, culture as an instrument of social redemption that has led to a mutual exchange of values and perspectives with particular attention to the subcultures of the web, social media, trap music and culture as means of expression of a human and existential unease, which lies invisible and unheard, but is actually real and deeply rooted. An uneasiness that extends outside the context of belonging and occurs in everyday life when it turns into adolescent depression, as analysed in Diptych (Thoughts on time perception): the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and isolation are revealed in the relationship between two adolescents, removed from the normal development of group dynamics and interpersonal relationships between peers, in a phase of life in which the perception of each event and of the passing of time itself appears enormously amplified, dilated, intensified. Significantly, the work unfolds like a diptych, borrowing the structure of a medieval sacred icon, one that could easily be closed and taken away in the event of a siege or sudden escape. The classic iconography of saints and martyrs are replaced by photographs of two young people during a day-long video call, like the previous and the next: a relationship that is consummated in the virtual sphere even if they are only a few kilometres apart. On the external walls of the aseptic diptych, specially made with cold materials such as steel and Plexiglas, two emojis (a fiery heart) and lyrics taken from the songs of American artists Lil Peep and Juice Wrld are laser engraved to build a new code of iconographic and verbal references for a new generation that no longer identifies itself with symbols and values belonging to an anachronistic past.

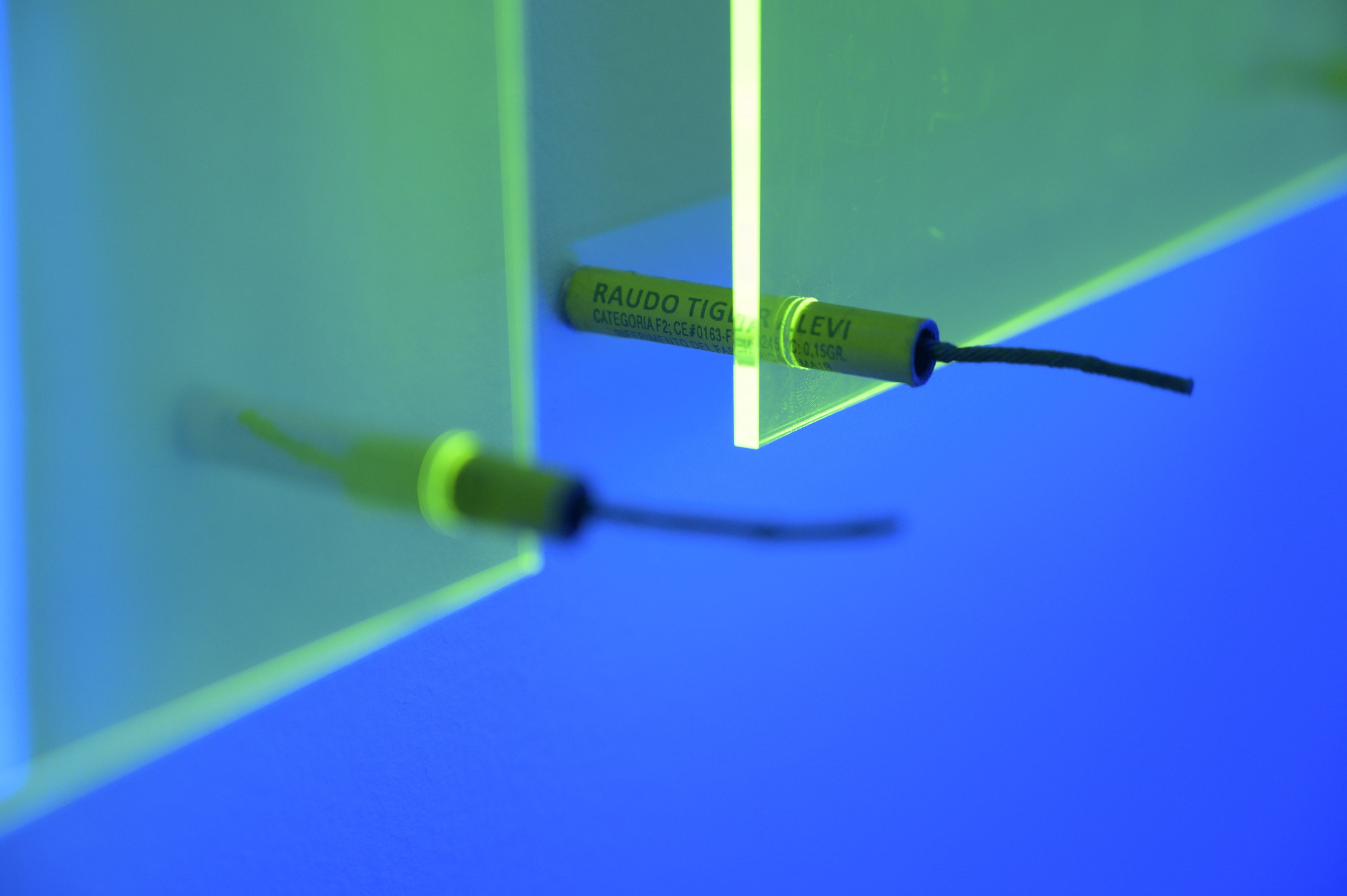

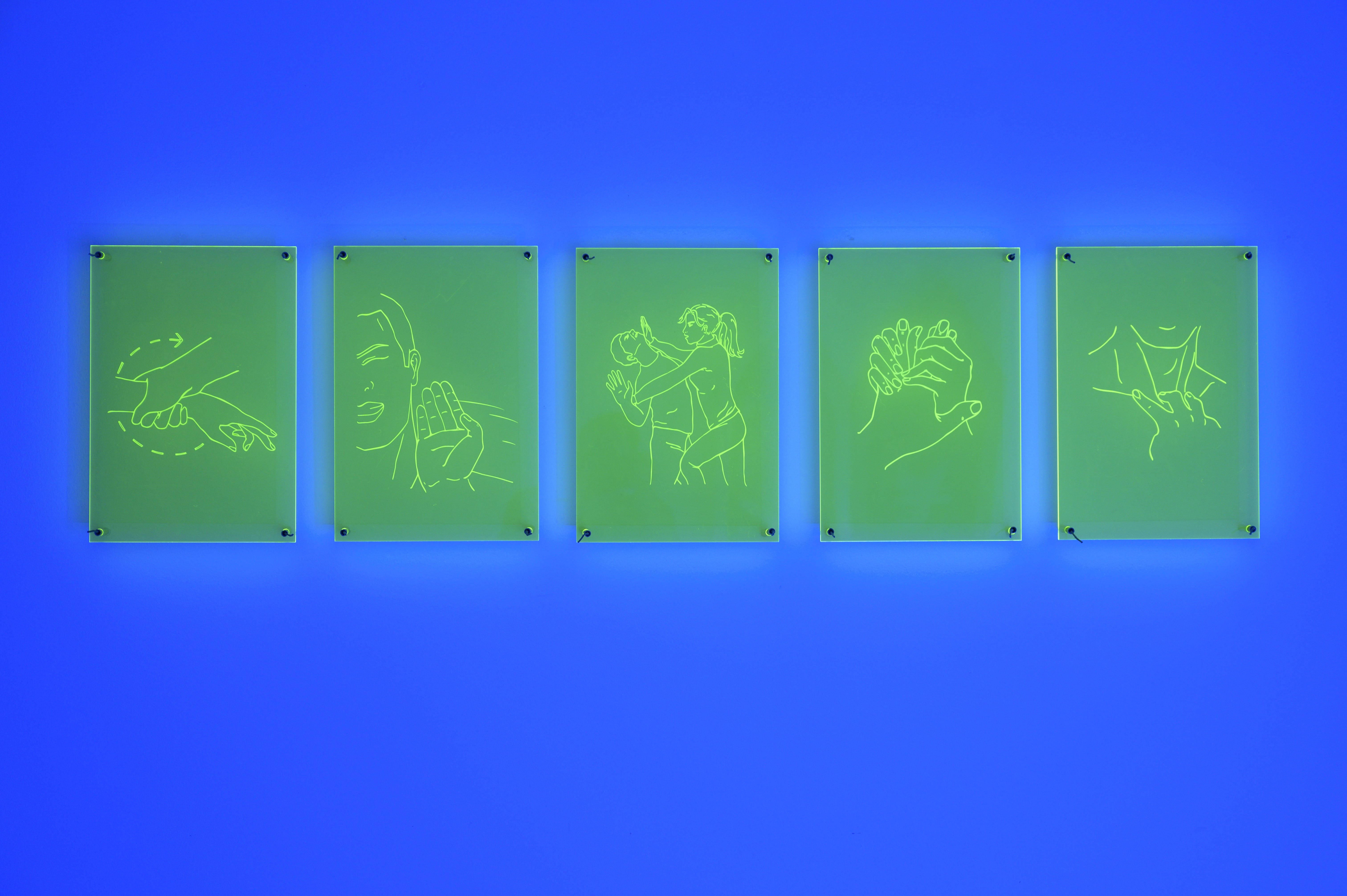

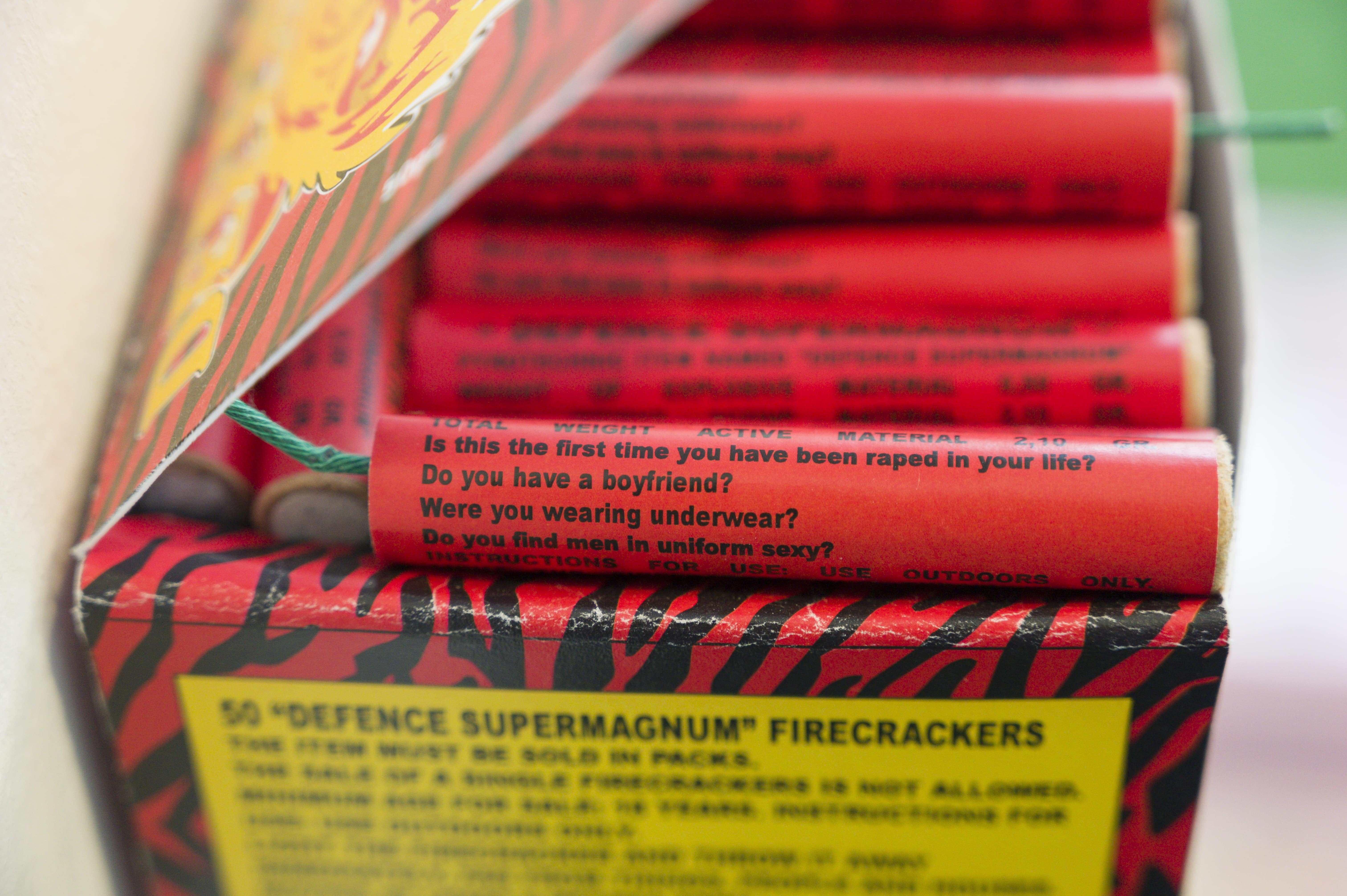

Numerosi anche i riferimenti alla violenza di genere, alla violazione -fisica e psicologica-, all’aggressione come condizioni disarmanti e senza appello: in SELF-DEFENCE, cinque incisioni su lastre di plexiglass fluorescente fissate al muro con petardi Raudi Allevi illustrano tecniche di difesa personale: metodi teoricamente ineccepibili ma completamente inefficaci dal momento che, nella maggior parte dei casi, chi si trova in queste situazioni si sente paralizzato e incapace di reagire. DEFENCE SUPER-MAGNUM, invece, è una scatola contenente 50 petardi Super-magnum marca Allevi ricoperti da un’etichetta che riporta alcune delle domande poste dal Gip Mario Profeta a due ragazze americane durante l’interrogatorio nel tribunale di Firenze che ha condannato i Carabinieri Pietro Costa e Marco Camuffo per violenza sessuale a seguito degli abusi perpetuati nei confronti delle due studentesse nella notte tra il 6 e il 7 settembre 2017. Gli avvocati della difesa, Cristina Menichetti e Giorgio Carta, presentano infatti 250 domande a ciascuna delle due ragazze, solo un terzo furono ammesse dal giudice, ma tra quelle che furono comunque rivolte alle ragazze leggiamo sui giornali: “È la prima volta che è stata violentata in vita sua?”, “Ha un fidanzato?”, “Trova sexy gli uomini in divisa?”, “Indossava la biancheria intima?”. Come una mina inesplosa e pronta per saltare, il petardo è pensato proprio per essere innescato e per mandare in mille pezzi con un botto ogni sovrastruttura che ancora si nutre di retoriche tanto violente quanto le azioni che sottopongono a giudizio.

There are also numerous references to gender-based violence, to – physical and psychological – violation, to aggression as disarming and without appeal conditions: in Self-Defense, five engravings on a fluorescent Plexiglas sheet fixed to the wall with Raudi Allevi firecrackers illustrate self-defence techniques, theoretically flawless methods but completely ineffective since, in most cases, those who find themselves in these situations feel paralyzed and unable to react. Defence Supermagnum, on the other hand, is a box containing 50 Allevi Supermagnum firecrackers covered with a label that reports some of the questions posed by the Judge for Preliminary Investigations Mario Profeta to the two American students during the interrogation in the court of Florence who sentenced the Carabinieri Pietro Costa and Marco Camuffo for sexual violence following the abuses perpetuated against them on the night between 6 and 7 September 2017. The defence lawyers, Cristina Menichetti and Giorgio Carta, in fact presented a list of 250 questions for each of the two girls, of which only a third was deemed admissible by the judge, but among those that were still asked them we read in the newspapers: “Is this the first time she has been raped in her life?”, “Do you have a boyfriend?”, “Do you find sexy men in uniform?”, “Were you wearing underwear?”. Like an unexploded mine ready to jump, the firecracker is designed to be triggered and to smash every superstructure that still feeds on rhetoric, which is as violent as the actions subjected to judgement.

Una mostra che assume quasi i toni dell’attivismo e della militanza, senza implicazioni di carattere politico o di fazione, ma con uno sguardo orizzontale sul mondo e sulla società contemporanea, portata avanti in maniera diretta e non filtrata, con l’immediatezza e la sincerità che solo all’arte oggi sono concesse. Una ricerca artistica che nell’alveo dei linguaggi più contemporanei, sviluppatisi a partire dagli anni ‘60 e diventati ormai necessità storica, si fa interprete di dinamiche e fenomeni sociali complessi, assumendo un ruolo attivo nel dibattito attuale e ragionando allo stesso tempo sull’incisività dei linguaggi dell’arte come strumento di documentazione e di comunicazione utile sia per operare un’indagine approfondita sul campo, sia per portarne i risultati all’attenzione di un vasto pubblico, entrando in contatto con il mondo anziché astrarsene.

An exhibition that almost takes on the tones of activism and militancy, with no political or factional implications, but with a horizontal look at the contemporary world and society, carried out in a direct and unfiltered way, with immediacy and sincerity that only art is granted today. An artistic research that, in the context of the most contemporary languages, developed starting from the 1960s and now converted in a historical necessity, becomes the interpreter of complex social dynamics and phenomena, assumes an active role in the current debate and, at the same time, ponders on incisiveness of the languages of art as a documentation and communication tool useful both for carrying out an in-depth investigation on the field, and for bringing the results to the attention of a wide audience, by coming into contact with the world rather than abstracting from it.